“Five years I’ve been at this office,” said my co-worker Mary, as she reached the peak of one of her impassioned rants. “No raises? No promotions? Am I not a good worker, Jim?”

“Among the best,” I said.

“Am I not passionate about the work?”

Mary, in fact, was the most passionate accountant I’d ever met. Over work lunches and happy-hour drinks, she could go on and on about the divine order of financial statements. At a Christmas party last year, she had recited a poem about the beauties of the double-entry bookkeeping system.

“Nobody’s more passionate than you,” I said.

“Yeah, Jim, I’ve got passion all right. Passion up the yingyang.” She’d had a few cocktails at lunch, which made her passion soar. “But I’ve got this crappy salary and no self-respect.” Mary was swivelling her desk chair so aggressively that hair fell from her messy ponytail. Finally, she spun the chair toward the boss’s door. “That’s it! I’m going in there, and I’m going to get what’s mine.”

So Mary marched into Old Man Feldenkirk’s office and demanded a raise. But instead of upping her salary, Feldenkirk fired her on the spot, and a week later he replaced her with a rhinoceros.

***

“What do you mean, a rhinoceros?” Mary shouted into the phone when I relayed the news.

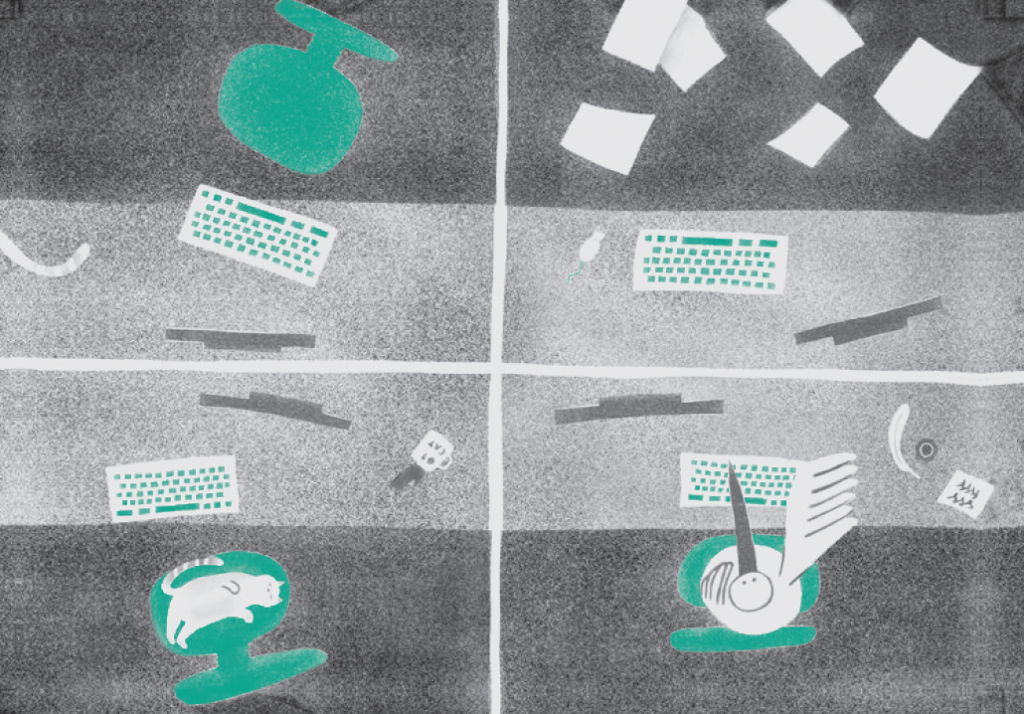

“I mean a rhino,” I said. “A big ole boy.” The rhino sat across from me at Mary’s old desk, wearing a grey button-down shirt and a red tie.

“How’s that supposed to work?” Mary demanded.

“Well . . . first off, they gave him an oversized keyboard.” I watched the rhino mash his hoofs into the giant keys.

“Is that a joke?” she cried.

“He’s actually pretty dexterous,” I said before she hung up on me.

***

The rhino’s name was Steve and he turned out to be an okay guy. He spent most of the day hunched over his computer, trying not to take up too much space. But sometimes, when deep in thought, like when he was trying to categorize a tricky expense, he’d sit back in his chair and tap his horn, the way a man might stroke his chin.

“So, Steve,” I said one day as he tackled a Subway sandwich. He always ate lunch at his desk. “How’d you get this job?”

The rhino looked up, a piece of lettuce stuck to his chin. “Conservation program,” he said tersely, then dove back into the foot-long. But my eyes stayed on him and soon he sighed, put the sandwich down and turned to me. “Poachers,” he said, tapping a hoof against his horn. “The number one cause of rhino death is poaching.”

“For humans, it’s heart disease.” I gave this some thought, then declared, “I guess yours is worse.”

“It is what it is,” he said with a shrug. “Back home, we have a saying: a rhino is born with a horn on his head and a target on his back.” He snorted a short, sad laugh, then added, “Conservationists have tried everything: harsher poaching laws, airlifting us to refuges, implanting us with trackers. But . . .”

“Poachers gonna poach.”

“You got it.” The rhino shifted in his chair, the hinges squeaking ominously under his weight. “One day some conservationists hit on the idea of removing us from the situation. They set up this program to teach us marketable skills — like data entry and basic accounting — and to integrate us into new environments. So here I am.”

“They give you that shirt and tie too?”

The rhino adjusted his Windsor knot and smiled. “Pretty sharp, huh?”

***

“A conservation program!” Mary shrieked from the pet food aisle of the supermarket where she’d been hired as a stock clerk.

“That’s what he said.”

“But what does a rhino know about accounting?” She jammed sacks of cat food into a stuffed bottom shelf, her face flushed from the effort and her hair pasted to her forehead. “Does he even care about accounting?”

“I don’t think so, no. But he’s a cheap worker, paid bottom dollar.”

“So was I! That was the problem! And so are you, aren’t you?”

“I am, yes.”

“You let them walk all over you, Jim,” she said as the store manager approached her about a protein shake spill one aisle over. “Honestly, where’s your self-respect?”

***

It turned out the rhino knew enough about accounting to get through tax season. I helped him out here and there, held his hand through a few tough returns, but he got the hang of things soon enough and cranked out more than a hundred returns before Tax Day.

“One hundred and three returns!” Feldenkirk said, clapping the rhino’s back during our post-season staff meeting. “An office record, Steve.”

The rhino nodded modestly and looked at the floor.

“You even beat Jim’s record of ninety-seven from three years ago,” Feldenkirk said as he turned to me. “Watch out, Jimbo — he’s coming for you.”

***

“You let a rhino outpace you!” Mary exclaimed.

We were in a pawn shop, where she was hawking a few things to make rent. She’d lost her job at the supermarket and seemed short on prospects.

“To be fair, he had the easiest returns.”

“Outworked by a rhino,” she went on, like she hadn’t heard me. “I can’t believe that. Seriously, Jim, where’s your self-respect?” Then she started haggling with the pawnbroker over her great-grandmother’s necklace.

“I helped him with a bunch of those returns, you know,” I said. “He’d have managed half as many without me. I’ve sort of taken him under my wing.”

“Is that right?”

“Of course. That rhino’s had a rough life. Always hounded by poachers. Can you imagine that?”

Mary stopped on the sidewalk to count her cash. “No. No, I can’t. All I worry about is heart disease.”

“The rhino needs guidance. He asks me dozens — hundreds — of questions a day. Especially now that we’re into corporate year-ends.”

“Well, sure, corporate year-ends can be tricky little buggers.” Mary stuffed the banknotes into her pocket. “Does this rhino even know double-entry bookkeeping?”

“Sure.”

“But does he know it? Does he recognize its majesty?” She scratched the side of her head; she seemed not to have brushed her hair — or teeth — in days. “Does he know that Goethe once said the double-entry bookkeeping system is ‘among the finest inventions of the human mind’? Does he, Jim?”

“I dunno.”

She shook her head. “You’d better let me come in and explain it to him. Maybe I can instill some passion in that rhino.”

***

A few days later, while Feldenkirk was at a conference, Mary came to the office, her hair nicely styled, makeup dabbed on her face. From the other side of the office, Joan and Gary came over to say hello and, when they heard why Mary had come, to spectate her passionate tutorial.

“The most important thing to realize about double-entry bookkeeping,” Mary began, “is that it’s magnificent.”

“Uh-huh,” said the rhino, keeping his eyes on his monitor.

“So agile, yet so robust.”

“Got it.”

“All of human commerce can be held within this simple system of debits and credits.”

The rhino frowned at me. “Is there a point to this person, Jim?”

Mary stepped right between us and barked at Steve, “What do you know about Luca Pacioli?”

“Uh . . . nothing.”

“Pacioli was the father of accounting. A fifteenth-century Italian monk. He was also” — and here she laid a hand on the rhino’s massive shoulder and shook him excitedly — “a great pal of da Vinci’s! Doesn’t that make perfect sense?” She clapped her hands in delight. “Great minds always find each other!”

“Who’s da Vinci?” Steve asked. “Another accountant?”

“What? No.” Mary looked my way, her left eye twitching. “Leonardo da Vinci. The painter and inventor.”

“Never heard of him.”

“What about Goethe? They teach you about Goethe?”

“What’s a Goethe? Is that a tax form?”

Mary smacked her palms on the desk, and the rhino’s oversized keyboard rattled. “No, he’s a writer! German.”

“I knew a German once. A poacher. Probably not the same guy.”

“No! Not the same guy!” Mary scrunched her nose and threw her head back.

As I watched her gaze plaintively at the ceiling, I was reminded of the time she got hammered and confessed that she often daydreamed about Goethe, da Vinci and Pacioli palling around in the afterlife, discoursing about art, science and the meaning of life. I knew that in her imaginings she was right there with them. But instead, she was here in this office with a rhinoceros.

With her eyes shut and her head still pitched backward, Mary whispered, “Double-entry bookkeeping is a testament to the human spirit.” A tear leaked from her closed right eye. “It contains a holy harmony. It’s among humanity’s greatest achievements. Like a stirring painting or a moving poem, it has launched us one step closer to the divine.”

The rhino turned to her and said, “Look, lady, I don’t really care about holy harmonies or human achievements. I just care about not being shot in the flank and having my horn sawn off, you know? So I just want to sit here and pump out these corporate year-ends.”

***

Mary slammed back a Scotch and threw the empty tumbler into a cardboard box in her living room. She was being evicted at the end of the week.

“That rhino has no passion for accounting!” she cried. Her face was tear-stained, her makeup smeared. Her hair had shaken loose as she paced furiously.

“Not a lick,” I said.

“Didn’t even know da Vinci! Never heard of Goethe!” She paused to stare at a framed photograph of Goethe on the wall. She brushed her fingertips against his cheek and choked back a sob. Then she resumed ranting. “It’s an outrage! A goddamn outrage! What does a rhino know about the human spirit?”

“Not much.”

“And you,” she said, stabbing a finger into my chest. “You agree to work with someone like this? Honest to God, Jim, where’s your self-respect?”

Then she threw back another Scotch and passed out between the cardboard boxes on the floor.

***

A few months later, I heard Mary had died of a heart attack. When I arrived at work, I went straight into Feldenkirk’s office to pass along the news. But instead of Feldenkirk, I was greeted by the rhino.

“I’ve been promoted!” Steve said from behind the big wooden desk.

What could I say? I congratulated the guy, then told him about Mary and asked for funeral leave.

“Ooh, no can-do, Jim,” he said, flattening his red tie. “We need you here, crunching those numbers.” Then he explained the upcoming pay cuts. “But you know,” he said, putting a hoof on my shoulder and ushering me toward the door, “your friend Mary was right about one thing. There’s a holy harmony to this business, isn’t there? Work hard, get promoted. A debit and a credit, huh?”

He laughed lightly, then pushed me out of his office.

***

At the rhino’s old desk, which was Mary’s old desk, now sat a bird with a broken wing who pecked at her keyboard all day long. Joan and Gary from the other side of the office had been replaced by a pair of stray cats.

As I sat at my desk, listening to the pecking and the mewling that had supplanted lively office chatter, I thought about poor, dead Mary. I imagined her in the afterlife, seated at a table with Goethe and da Vinci, spending eternity in passionate dialogue.

Better off dead, I decided, because down here, in this office, there was no place left for a person of passion.

Comments are closed.